Tardiness and Poor School Facility Conditions are Interconnected

The California Department of Education’s new California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) provides loads of insight for state and local leaders into what makes for healthy school environments…and what doesn’t. A perpetually overlooked aspect of school health and overall school climate is the condition of a school’s facilities and grounds. Here at the Center for Cities + Schools, we’ve looked at this issue in a number of studies – and we have found alarming patterns of underinvestment in California’s K-12 facilities , which raise serious questions about whether or not children are attending school facilities that are healthy, safe, in good repair, and promoting high quality teaching and learning. A new report from WestEd, using the CHKS data finds that 32% of California’s 11th graders describe their schools as having low quality physical environments. The study finds that student perceptions of the quality of their schools’ physical environment are strongly related to the demographic composition of schools: lower rated schools have greater percentages of kids on free/reduced priced meals and higher expulsion and suspension rates. [CLICK HERE to view the full report.]

The disparity in school facility conditions may be having disparate impacts on students throughout California. In our work with high school students through UC Berkeley’s Center for Cities + Schools Y-PLAN (Youth – Plan, Learn, Act, Now!), I have seen firsthand the unique ways that school facility conditions affect students. I’d like to illustrate how these connections are sometimes hidden…but nonetheless impactful on students.

“How many of you have been tardy to a class this year?” The principal of an inner city California public high school pressed students during the question and answer portion of a presentation last month on ways to improve school climate.

The hands of four of the five presenters slowly and sheepishly raised into the air. These students had spent the previous two months researching school climate and selecting topics to tackle, from security guard relationships to student stress levels to tardiness to class. They mapped the school grounds, perused the school’s survey, drafted their own and surveyed over 200 of their peers, and conducted interviews with students and educators alike as part of the Y-PLAN methodology. Their presentation was packed with data, but lacked the personal connection, and their principal knew to push further.

“You’re all conscientious students. You know if you’re late to class you fall behind, and you get detention. Why are students still coming to classes late?” His genuine question opened the floodgates to the information he sought. The five presenters, with the help of the other 35 members of their class, chimed in with causes of tardiness that have been echoed by Y-PLAN students from struggling schools serving primarily low-income students of color from across the state and the country.

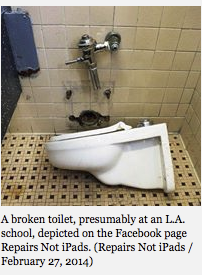

Two primary issues that emerged as the most important in this school were the quality of the lockers and the bathrooms. The lockers are old, broken, and don’t lock[JV6] . With many dating from 1965, they are older than the students’ parents. If students use broken lockers, their belongings get stolen. If their textbooks get stolen, they have to pay for them. To avoid this, they share with friends, which can cause them to be late as they wait for the friend to arrive and open the locker before navigating across the large school campus to get to class.Secondly, the bathrooms[JV7] are in a state of disrepair. Very few stall doors lock, or even close, when they exist at all. Toilets overflow and flood the floors. In this particular school with more than 1500 students, students reported that only one stall in one girls’ bathroom was currently working properly. Students chose to wait to use the bathroom when necessary, and deal with the consequences of tardiness to class.

The principal listened intently, tracking notes as the students spoke. After a moment of silence, with a concerned tone, the principal asked “Why haven’t you told us? We don’t use these facilities, so we were unaware of the condition.”

The students hesitated before responding. His question was genuine, and one shared by caring educators everywhere. Yet the answer seemed so obvious to every student in the room that they weren’t sure where to begin.

“We didn’t expect anything to be different.” Students in our most struggling schools see images of new, clean school facilities in other places, yet walk the halls of their decrepit buildings, with no windows, with trash cans collecting rainwater leaking through ceilings, with graffiti covering their walls, with trash lining their walkways, heaters and air conditioners that don’t function, doors that do not close properly, in classrooms without enough desks, or space to put them.

Y-PLAN challenges students to tackle a school-based problem, from tardiness to recycling to school spirit. They collect primary source data and analyze it critically. They start with disparate questions, but their recommendations typically converge on one specific theme: when we allow our young people to attend schools in these conditions, they learn that we do not think they deserve any better. When the students who identify their schoolsand grounds as unclean, their buildings and yards as not in good condition are disproportionately eligible for free or reduced student lunch and are overwhelmingly African American and Latino, we reinforce their understanding of where our priorities lie. When we show them through our choices that we don’t think they deserve any better, how can we hope they still expect better for themselves?

The relationship between the quality of a school’s physical environment, its academic and school connectedness outcomes, and the racial and socio-economic background of the students illuminated by the recently released California Healthy Kids Survey will not be new information for the students who admitted that their schools and grounds are not clean and tidy, that their buildings and yards are not in good condition, and that their classrooms are so crowded they cannot concentrate. The bigger question is whether and how we will address these disparities and prove to our lower-income students of color that we know they deserve better in our hands.

The relationship between the quality of a school’s physical environment, its academic and school connectedness outcomes, and the racial and socio-economic background of the students illuminated by the recently released California Healthy Kids Survey will not be new information for the students who admitted that their schools and grounds are not clean and tidy, that their buildings and yards are not in good condition, and that their classrooms are so crowded they cannot concentrate. The bigger question is whether and how we will address these disparities and prove to our lower-income students of color that we know they deserve better in our hands.

Click here for the full 2015-2016 CHKS School Facilities Results report.

Amanda Eppley is the Y-PLAN Program Director at the Center for Cities + Schools at UC Berkeley.