Student and Teacher Transformation Through Y-PLAN

I spent the last ten years supporting teachers to implement project-based learning (PBL) in the Oakland Unified School District in Oakland, California. During that time, we grappled with one of the critical challenges of PBL: how to make the learning experiences both relevant to students and rigorous as defined by grade level standards.

One of the most successful answers to that question was our partnership with the Center for Cities + Schools at UC Berkeley through their Y-PLAN initiative. These projects always included research on timely and important questions, such as how to create a sustainable Oakland or how to reimagine public safety. Students were then pushed to produce high quality policy briefs and poster presentations that were shared with local planning officials and elected representatives at classroom showcases and at civic venues like City Hall.

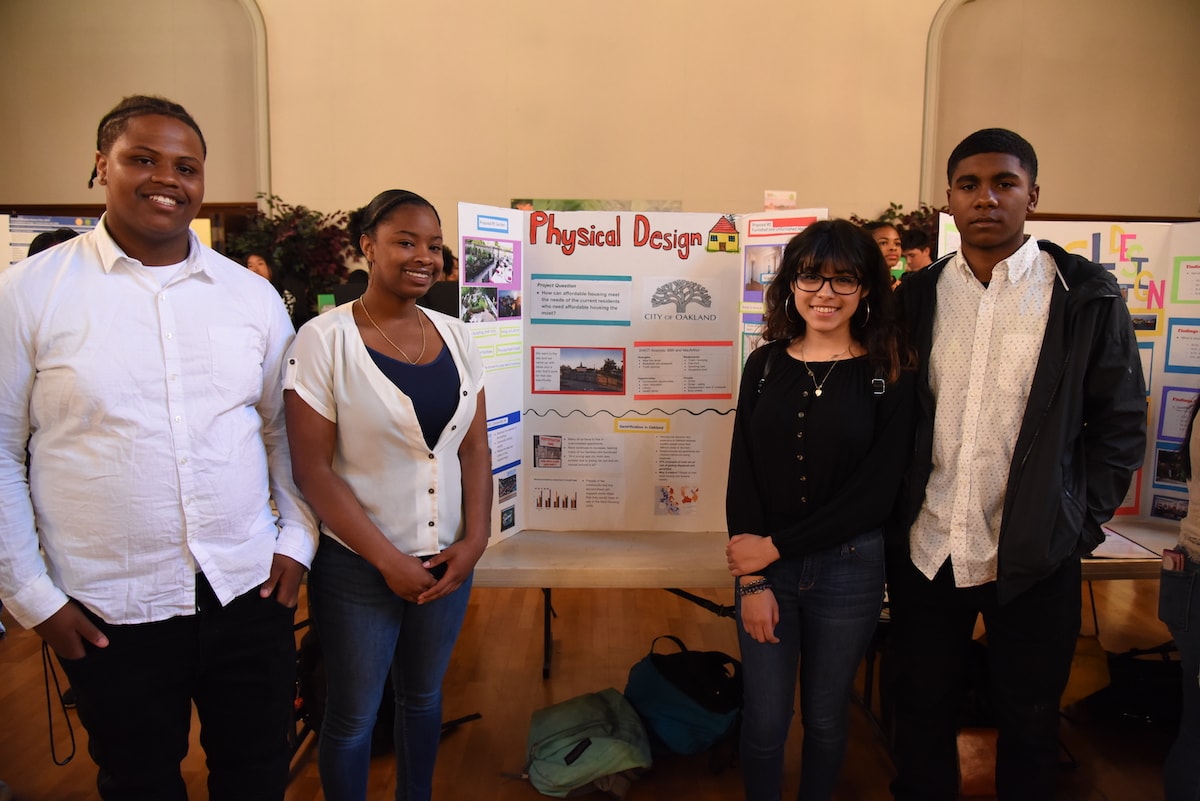

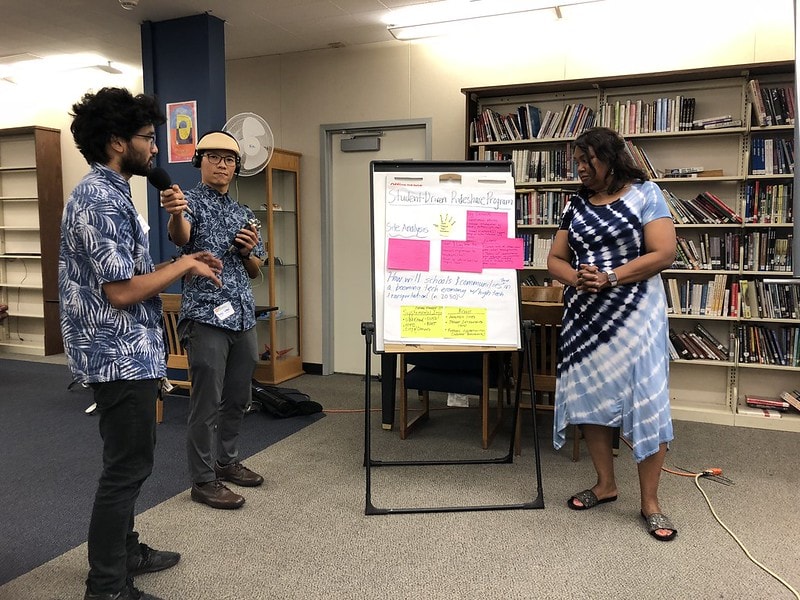

Students from Oakland High School presenting their project proposals as part of Step 5 in the Y-PLAN methodology.

Often, students cited these learning experiences as the most valuable ones they had in high school. And the learning wasn’t just for the young people; behind the scenes, teachers were learning new ways of being in the classroom. Each year, Y-PLAN staff led teachers through a Y-PLAN mini—a condensed version of the steps that they would take their students through. In other words, teachers first experienced Y-PLAN and, second, facilitated their students through it.

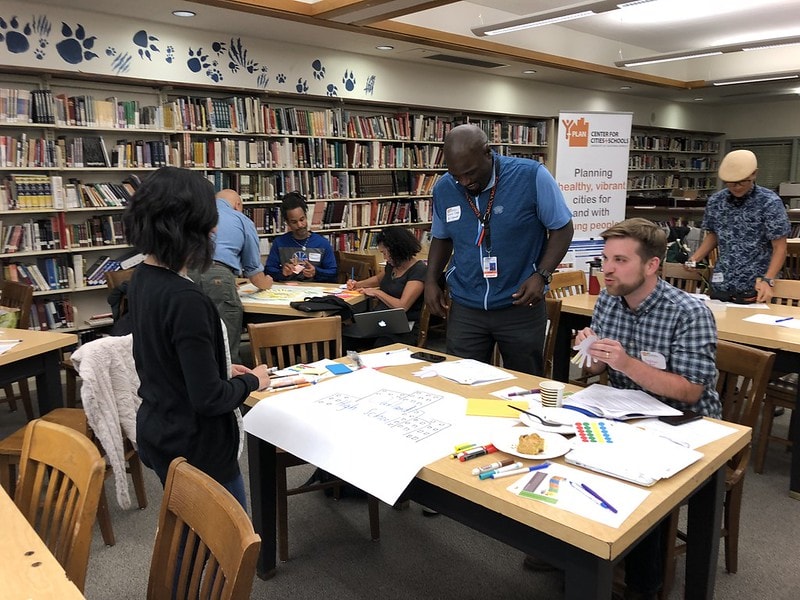

OUSD teachers working through a professional development training on the Y-PLAN methodology.

Through professional development and direct experience leading a Y-PLAN project, teachers gained new insights into teaching. Here are some of those learnings:

Authentic questions come from the community, not only from a teacher

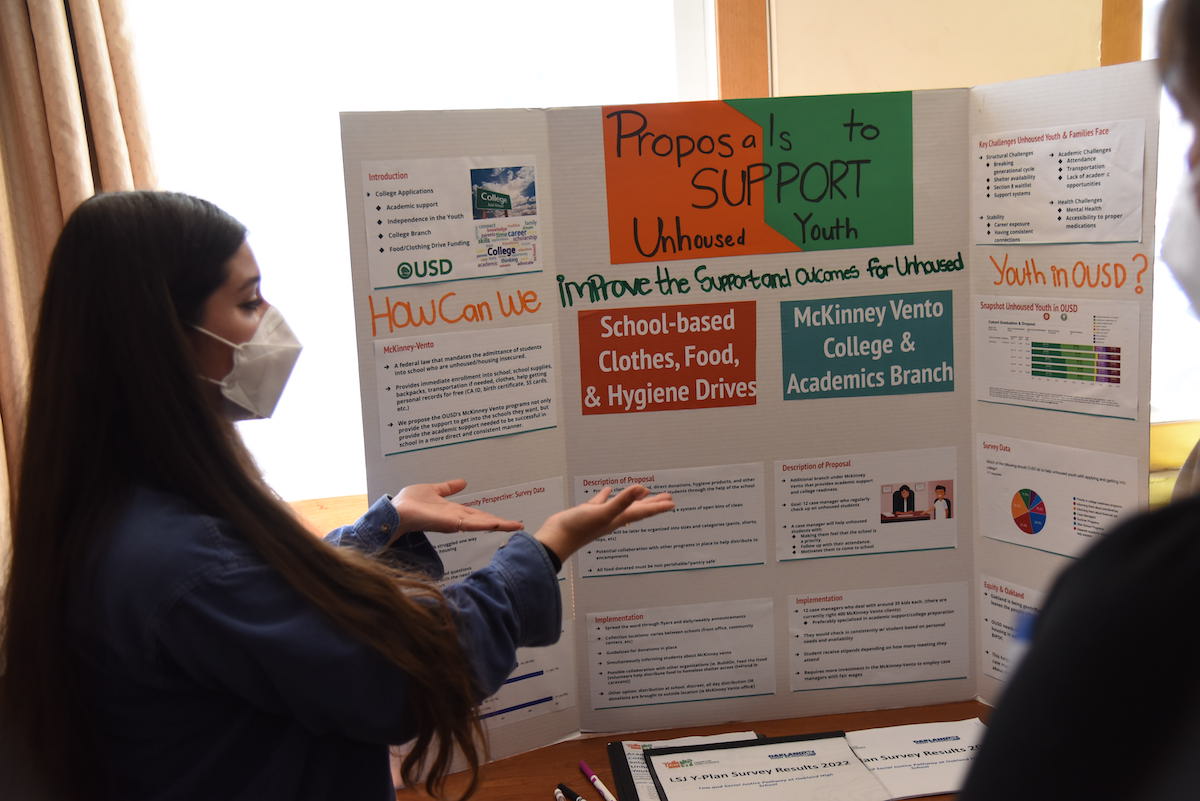

Teachers might start a unit with an essential question, but those questions often get lost in the day-to-day instruction. They may have spent countless hours over the summer carefully constructing an essential question, yet they stop referring to it because they sense the kids frankly don’t care. In Y-PLAN, questions emerge, not from a teacher’s brain, but from the needs of the community. When a civic leader comes to class to talk about the challenges their community is facing, such as supporting unhoused youth, the project’s question takes on new significance.

Students need to get out to see, touch, and hear about the issue

It’s a lot of work to get students out into the world on a field trip. But the payoff is real. When students see the vacant lot where their client is planning to build affordable housing, they have a tangible sense that their recommendations are more than another classroom assignment that will disappear under a teacher’s growing stack of student work. Teachers in Y-PLAN know that their students need to leave the classroom to make societal issues and their potential solutions come to life.

Students have valuable perspectives and creative ideas

As much as we may criticize fill-in-the-blank activities, it’s hard to break the practice. It’s even harder to break the mentality that teachers and students are in rigid roles where the teacher possesses knowledge and the student needs to learn it. Sure, there are times when teachers do actually have information to impart; however, we fail to provide enough opportunities for students to generate their own ideas. The Y-PLAN research and charrette process asks students to gather information from the community, make sense of it, and generate creative solutions based on research and their own creative thinking. Y-PLAN holds up the youth perspective as valuable in and of itself.

Teachers reflecting on how Y-PLAN has shaped their role as an educator at the 2019 CC+S Symposium on the Power of Civic Learning for Resilient Cities

Teachers embody new roles as facilitators of learning

Teachers who have participated in Y-PLAN invariably see their role in the classroom differently. They embrace the identity of being a facilitator of learning rather than a bank of knowledge. They encourage students to sit in groups and have lots of student-led conversations. They ask students to share their knowledge through presentations rather than worksheets or tests.

And here, we return to the dilemma posed at the start: does the relevance of these projects come at the cost of rigor? In my experience with Y-PLAN, relevance and rigor are cooperating, rather than competing, factors. When others express concern about whether students will be ready for the demands of college, I offer the perspective that students will develop college-ready skills when they see a purpose in doing so. In other words, students develop academic competence as researchers, writers, and presenters not for a grade or test but because they see their work as vital to addressing the issues facing our world. And for students to engage in meaningful work, teachers need support and encouragement to teach differently.

For powerful practices in leading teacher professional development, check out Young Whan Choi’s new book, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning.

About Young Whan Choi

Young Whan Choi (he/him) has been a teacher in South Korea, New York City, Providence, RI, and Oakland, CA, during which time he developed expertise in project-based learning, curriculum design, and culturally relevant teaching. Currently, he teaches the next generation of social studies educators at UC Berkeley. He has a new book on teacher professional learning and has written for various publications including the Washington Post’s AnswerSheet, EdSource, The East Bay Times, and UCLA’s Xchange journal. He produces and hosts The Young and the Woke podcast.